Written by Andrew Barney and Heracles Polatidis from Uppsala University

Everyday people need to make choices. Many, many choices. So many that they may not even consciously be aware they are making those choices. The choices range from the trivial, which pair of socks should I wear? To the life changing, should I quit my job? When people make these choices, they do so based on what they think is best for them, or put another way, using their preferences.

Are people always aware of their own preferences? In many cases the answer may probably be yes. A person may pick socks because they are blue, and they prefer blue socks to red. But what happens if that person, like most people, has competing preferences? They prefer blue socks, but they also want warmer wool socks and socks that fit well. The blue socks, while clearly a delightful blue, are not wool nor do they fit particularly well. The red socks, despite not being blue, are both wool and fit well. Is this person facing a dilemma where they will be stuck considering for hours, unable to pick a pair of socks to wear?

Probably not! People automatically measure their choices against their preferences and will make the best decision for them based on this silent, and often unconsidered, process. Often, people do not need any help with this process and can successfully identify the decision that is best for them, but what happens when things start becoming complicated? When there are many different choices and many different, and competing, criteria for judging the choices? Say for instance when choosing a car? A house?

Governmental entities face decisions as well but, unlike individuals, they maybe do not have the same intrinsic feel for what their preferences actually are. How do they figure out where their preferences land? On top of this, the entity may have multiple sets of preferences to consider from those impacted by the decisions to be made on top of their own set of preferences. These entities need to decide how much value these different preferences have and how, and even if, they should be integrated. Definitely not as clear or as automatic as when you pick a pair of socks!

These difficulties are perhaps best understood through an example, let us say a government is planning to build a much-needed desalination facility. They are given a list of a half dozen possible locations for the facility and they need to pick one. The different locations will have different environmental impacts, construction costs, future operation costs, differing technical requirements and social impacts. The government thinks it knows where best to put the facility but there is strong opposition from environmental groups who feel the facility is too near a nature reserve, so it changes to the second ‘best’ location but business owners are concerned by the facility’s nearness to a popular tourist destination. The government decides the third location might be too remote to actually be feasible. Similar problems pop up for the other locations as it turns out no one can agree on where the best location is!

What should the government do? Should the project not be built despite the need? How should they make the decision on where to put the project? Are all the impacts of the project equally important? To whom? Plainly, things get complicated quickly when planning for and around energy and the environment. It is difficult to keep track of all the different criteria and options going around. So, what can a government do?

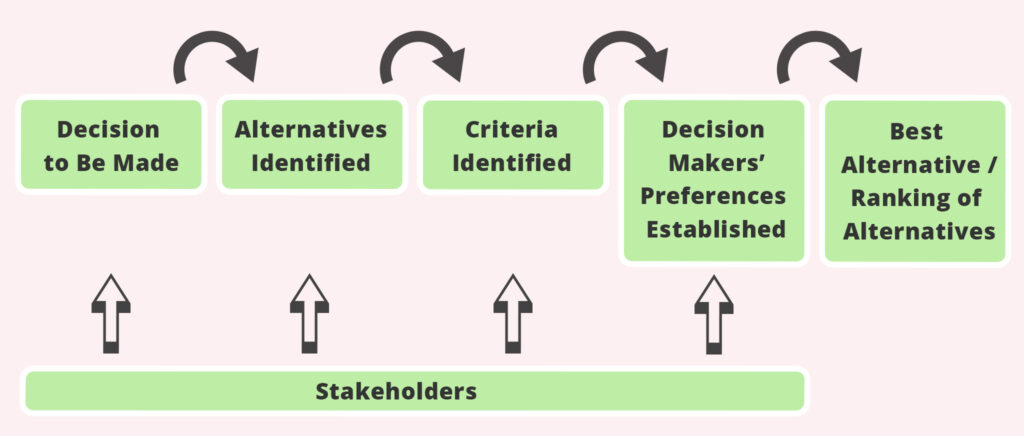

Fortunately, methods have been developed to help decision makers evaluate their choices when faced with many different criteria. These methods are, perhaps unsurprisingly, called Multi-Criteria Decision Aid (MCDA) methods! While their specific approaches differ, these methods give users a means of addressing complex, multifaceted decisions in a systematic way. Applied to the example above, MCDA can allow the decision maker to assess the different preferences stakeholders have for different criteria and ultimately provide, depending on the method used, either a best alternative or a ranking of alternatives for the placement of the desalination facility or grouping of the alternatives to specific categories like good, average and not preferred, etc.

The process of MCDA begins with the identification of a decision that needs to be made, in this case where to put the facility. Once the decision to be made has been identified the available alternatives, along with their consequences, can be found. In the above case, this would be the listing of potential locations for the facility and their respective impacts. After those have been identified, the criteria to be used when comparing the alternatives also need to be identified. For our case, the following criteria might be used, among others: how much environmental damage does the facility’s construction and operation cause, how near is the location to touristic sites and how far is the location from end consumers. All the proceeding steps require input from relevant stakeholders, who also must be identified and engaged. We will say that environmental groups, business owners and the local government are the key stakeholders. Once everything is in place, the different alternatives can be evaluated against the decision maker or makers’ criteria using a MCDA method to identify the best available option, or a ranking of the options.

So, given what we have above, we know that we have six possible locations, and we are evaluating them using three different criteria that have been given different preference weights by three different stakeholders. Using a MCDA method, we will be able to combine all of this to, propose a way forward!

Within the REACT EU Horizon 2020 research and innovation project, MCDA is used for exactly this. Future energy scenarios including both production and storage technologies, for instance solar PV and batteries, are generated explicitly for three islands in the EU. Once the scenarios have been generated they are evaluated using different environmental, technical, economic and social criteria to generate a ranking for the scenarios that can be used to inform the choice of which energy system should be built on each island.